ARTIST SPOTLIGHT: BEATRIZ CORTEZ

Our next artist does not need any introductions. From her recent participation in the collective XMAP: In Plain Sight art project this past July to her latest commission depicting an ancient boulder at New York's Rockefeller Center, Beatriz Cortez has turned her traumas of displacements into art - all while examining the link between the pre-existence and what the future holds.

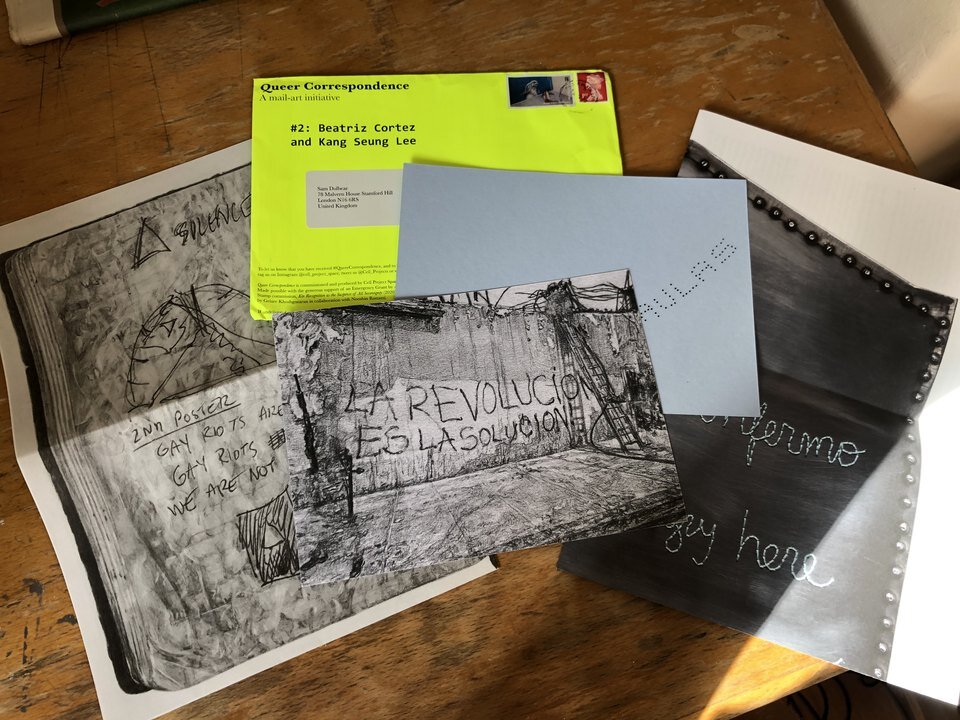

Seemingly, the Los Angeles based artist has been keeping busy in the last few months, not just independently though - but collectively, during a time where it matters most. Community plays a huge role in Cortez's work. Take her Queer Correspondence commission as an example, for the Cell Project Space in London, where she and multi-disciplinary artist Kang Seung Lee have a back and forth paper mail conversation - some that consist of drawings, others in written letters; on discourse around the AIDS pandemic, war and migration. Within the letters, you can sort of feel their depleting energies and/or coexistence.

Watching from afar, the most intriguing part about Cortez's work as of late is, not only is it timely but a result of embracingly working as one, and together with fellow artists, in Los Angeles and elsewhere. For this interview, Cortez walks us through her latest projects and relives her time during lockdown as a reflection of today.

(Q) Talk about your part in In Plain Sight. What made you choose "NO CAGES, NO JAULAS" as your message aside from the obvious reasons of confronting ICE/Immigrant enforcement in the U.S.

There is so much that I wanted to say about the detention centers where immigrants are held in subhuman conditions for profit. However, each artist had only 15 characters to express what we wanted to say. Brevity is not my greatest strength, but I decided to speak about an urgent matter, the detention of children in cages. I chose the bilingual phrase "NO CAGES NO JAULAS" because our communities have suffered one of the most despicable acts: the separation of children from their families. Our children are being held in refrigerated cages surrounded by chain link, covering their bodies with mylar blankets, growing up alone, feeling abandoned - without being able to satisfy their most basic needs physically and spiritually. They need to be released to their families who love them and miss them, and to their communities so that we can be made whole again and so that they may heal. In addition, I wanted my statement to be both in English and in Spanish, like life in Los Angeles.

(Q) Lots of your work broaches on subjects around migration and memory. Can you tell us more about your upbringing and how it's influenced your work? What does migration mean to you, from personal experiences?

I grew up in the war in El Salvador, in spite of the war I had a happy childhood. I always imagined myself as an artist, and I was surrounded with creative people who inspired me, who read literature, who sang, who made art, who built things, and who played music. I left suddenly in November 1989 when I was about to turn 19 and was about to finish my first year of college. I was in art school. So the war and migration impacted my work but also my experiences of growing up in San Salvador, its landscape and materials, the ways in which I build things, the types of plants that are in my imagination, etc.

(Q) Are you working on another series, or body of work addressing immigration and displacement at the moment? It doesn't have to be on display. Or tell us more about "Queer Correspondence" and how it relates to your current work/timeline?

I worked on a new series of sculptures for a show titled Becoming Atmosphere that's on view at the 18th Street Art Center gallery in the Santa Monica campus. This show is a collaboration with another artist and friend, Kang Seung Lee. In many ways, some of the materials that we included as part of our participation in Queer Correspondence were part of the conversation that we were having as we were making the work for Becoming Atmosphere. It is a reflection about disappearing, about willing to step outside our identities, about imagining becoming other, about collective care, and about breathing. At the same time, our work for Queer Correspondence was a reflection about the pandemic, about being together in spite of the isolation, about Black Lives Matter, about immigrants exposed to Covid while on detention in a system for profit, about breathing, and about how our bodies are porous, we are entangled with each other, we are breathing each other. My letters to Kang for Queer Correspondence end with the experience of standing by the lake in MaCarthur Park, in Los Angeles, watching the planes type our phrases in the sky after having spent the day making a mural on the ground with the members of different community organizations.

(Q) Walk me through your days in quarantine - are you still in lockdown? If so, what have you been working on to keep you busy during these tough times?

I have been fortunate to be busy with creating art and writing, imagining things for different projects. The pandemic has meant that I have had to work with much smaller teams that some of my projects needed, and that sometimes I have had to work too many hours and have been quite overworked. However, I have been working, often at home and also in my studio. I have written a catalog essay, and given a few public lectures. I worked on the materials for Queer Correspondence, and I worked intensely in the making of my large-scale sculpture Glacial Erratic, which was on view for Frieze Sculpture at Rockefeller Center. In late August I started to teach. I am a professor at California State University, Northridge. I am currently teaching classes on the Central American transnational experience, the Central American diaspora, Central American literature and Afro-Caribbean cultures and identities in Central America. Now, I've been making the work for the Becoming Atmosphere show.

(Q) Clearly you have been active during the pandemic which is much needed I'm sure, but walk me through your days in lockdown if you can recall? What was that like? And how is it different from today, where it's safe to go outside (with restrictions of course)?

My days in lockdown allowed me to rest, to sleep extra hours. I walked quite a bit, inside my house, on the patio. I also spent time writing and reading on my hammock, and making art at the dining table, in the kitchen, in the living room.

(Q) Where did you exhibit your works last? And when's your next presentation?

My last show was Glacial Erratic at Frieze Sculpture in New York. My current show is Becoming Atmosphere at 18th Street Art Center in Santa Monica.

(Q) Talk about your work that will be on view soon - tell us more about the Glacial Erratic rock you speak of?

Glacial Erratic was a large-scale sculpture that evoked the boulders that were moved to what is now New York city by the melting glaciers during a prior episode of global warming millions of years ago. It engages with the idea that these boulders have different mineral content than the landscape around them, that they come from elsewhere, that they have migrated, that migration is natural, planetary, millenary. But also, it is a conversation about the atmosphere that we are all breathing in, and breathing into, it is a conversation about how the atmosphere impacts all the organic beings and how we react to the atmosphere. So this metal sculpture was not sealed, it was exposed to the elements, reacting to the environment. In addition, the sculpture was about steel, as a material that comes from under the ground, that is organic, is alive, and yet we imagine it as solid and permanent, as part of a shiny modernity. It is a sculpture about how modernity crumbles, and new modernities emerge all the time.

Thank you very much for this conversation.