In the Studio with Gisela McDaniel On Her Practice “Talking Story” and Research

For CHamoru artist Gisela McDaniel, returning to her ancestral homeland is far more than just a trip home—it’s a sacred act of reconnection. Guam, where most of McDaniel’s paintings are rooted, is a place where research and healing converge at the core of her practice. It is here that she works with CHamoru Yo’amte healers to inform her work; that to her, these relationships are “not just on my art but on a visceral, immediate yet somehow timeless sense of who I am, who my people are, and where my family and I come from.” A true reflection of the her ongoing dedication to understanding her heritage, the stories of her people, and the experiences of her sitters; the artist’s work beyond the studio is just as equally as important to highlight, inextricably linked to cultural preservation, healing, and connection.

Through portraiture and interviews, McDaniel creates a space for marginalized voices—particularly survivors of abuse and sexual trauma—to be heard and seen on their own terms. Often depicted in reclined positions, her sitters are painted in bright colors—reds, yellows, and pinks—a symbol of the body and life, and are carefully rendered to honor their stories. Now, McDaniel uses "heated" colors to pay tribute to the lasting trauma caused by U.S. nuclear testing in the Pacific, particularly in Micronesia. While Guam was not a nuclear test site, it was exposed to radioactive fallout from tests conducted in the Marshall Islands between 1946 and 1958. Through this, the artist returns to her people, especially CHamorus in Guam, whose lives were irreversibly affected by such events.

Her recent work, now featured in the Hawaii Biennale and soon in her first solo U.S. museum exhibition at the Ogunquit Museum of American Art, blends personal experience with her recent travels to LA and Detroit where she began her work after completing a BFA at the University of Michigan. Her research reveals a deep, personal connection to her heritage, family, and the healing power of “talking story” - an Oceanic cultural practice that creates community and a safe space to share heavy stories of oppression, trauma and colonization. Her canvases incorporate shells, beads, jewelry, and personal objects, adding a tactile and intimate layer to each piece, accompanied by sound elements that the artist jests feel as if she’s “booby trapping” approaching viewers feature recordings edited by the artist and activated by motion sensors by viewers.

art currently visits McDaniel’s studio in Brooklyn, and discuss the extensive research that goes behind her studies on healing and reclamation through audio, space, and consensual artifacts as seen in her portraiture paintings.

How does this connection to your ancestral history influence your artwork and could you tell us about your experience working with healers in your recent trip to Guam?

Every single encounter or piece of knowledge that traditional healers share with me, whether it's a Saina (Elder) like Mama Chai (a Yo’åmte in her eighties) or her apprentice, my dear friend, Vinessa (who’s closer to my age), influences and shapes me and the work I make. So, I’d say that my experience with indigenous CHamoru healers deepens and connects me to my ancestral history as living history that’s never really been in the past but is very much alive in the here and now. All of that goes into the work I create as well as who I experience myself to be.

Working with and being able to learn directly from CHamoru Yo'åmte healers is an honor and something, as I’ve said before, I consider precious. I’ve been able to spend time with indigenous healers as they locate, identify (for me) and/or carefully tend to medicinal plants used as åmot (medicine).

I’ve experienced and observed healing forms of touch (massage) to treat a variety of illnesses and received a blessing that included oils mixed with perfume. I can still remember a moment when a blessing was being spoken over me, that cacophony of sounds that had just included several dogs barking, roosters crowing, and even the wind gusting around us suddenly going absolutely silent, standing still.

Aside from my own experiences, I’ve witnessed the community’s deep respect for our CHamoru Yo’åmte’s continuing presence on the island and the way they bless and bring several generations together. But in the end, though, I think it’s even more important to let a Yo’åmte speak for themselves:

“The value of plant medicine and traditional healing is… incalculable. [I]t's sacred knowledge that's been held onto for generations and for generations… and [more importantly] it's a system that was brought over by us. [I]t's been incorporated with.. other traditions, but the fact remains that: it's ours, it belongs to us. And it's been proven to work over and over again. You know, we don't need a Western institution to tell us what's ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. We know that it works because it's worked time and time over again. The value of plant medicine and traditional healing is that it's connected to the land. It’s what connects us to the land. This is how we continue our relationship with the land and the spirits and how we can, as a community strive to keep these traditions alive for the sake of our health.” - Vinessa Dueñas, Apprentice to Yo’amte Mama Chai

How do you create a safe and healing space for your sitters, especially considering the vulnerability of sharing such intimate experiences?

Making sure the process is fully understood beforehand and that everyone is comfortable is key to my practice. I either visit someone’s personal space or open up my own, depending on what they want or are able to do. People then share as much or as little as they want which can be edited as needed (should they have any further thoughts or feelings after we’ve met).

In a very real sense, they authorize what is shared with their piece, which is key. At the same time, at least to some degree, I hope to try to make the process enjoyable if not fun when possible, at least as it naturally unfolds between the sitter and me. As someone who was extremely shy growing up, I think about what would make me feel comfortable and try to create a similar vibe.

At the same time, people don’t sit for a painting every day, so I’m mindful that it is a special moment for them, and still, always for me, as well. I frame the experience by suggesting that it’s their experiences, their image, and their memories that are being placed into history. Then I ask them to consider how they wish to present themselves; how they wish to be remembered. Finally, they select the image I will work from, so again, they know exactly how they will be portrayed going forward.

Recently, I had a friend compare the experience to the feeling of a sleepover, where you stay up late and maybe even “overshare” with your friends. But still, even if you do happen to overshare, you know you’re “safe” because of the respect and trust based on the relationship. I think and hope that for most of my subject-collaborators, that framing might resonate.

Finally, the practice of “talking story” from the Pacific is an integral part of my artistic and cultural practice. Talking story is basically a way of building community where the sharing of one’s story makes us safe(r) and creates a form of protection within the community because of what we now share collectively.

In your art, the subjects don’t necessarily appear as survivors, which creates a powerful contrast with the deeper themes of healing and acknowledgment. But then again, what do survivors look like?! How does this choice help to reflect the broader conversation about the power of being heard and seen in the healing process?

Every person is so much more than specific moments in their lives. When I edit audio following a sitting/interview, I focus less on how events shape people, a person, and more on how they/we can and do choose how to move through the world. This shift in understanding is crucial because it diminishes, if not destroys, the power of trauma to have the final word and focuses instead on the whole woman, femme, person. So many portrayals of violence emphasize the violence rather than the human person. I want to tell stories about people. And I especially want to ensure that the people whose stories I’m honored to (re)present in my work are narratives that they wish to share and that others might want to hear.

Could you tell us about your new works at the Hawaii Biennale and what the inspiration was behind it?

Oh, definitely. It was a tremendous honor to be invited to submit three pieces and the untitled audio sculpture. As a daughter of a daughter of the CHamoru diaspora, it will always be a pivotal moment in my work as an artist because my work was part of a larger Oceanian gathering of artists, sculptors, poets, dreamers, activists and storytellers. As for the works…

The large canvas depicted Mama Chai seated between her two apprentices, including her daughter, Mar, and Vinessa (quoted earlier). The three were seated outside of Sagan Kutturan CHamoru (Place of Culture) a special village and nonprofit in Guam that provides spaces for leading and upcoming traditional practitioners of CHamoru art from weavers to carvers and, of course, indigenous healers. The piece is entitled: “Make Your Heart Strong (Amot)”

The second piece entitled, “Inafresi (Offering)” depicts Lasia, a CHamoru Transwoman and fierce Community Leader, who organized the first (official) Guam Pride on the island. From decades of rejection including an inability to gain employment to working on key legislation protecting “Gela” (Gay) rights on island, Lasia’s name, contributions and story are of special note given wide acceptance of gender fluidity in many (ancient) Oceanian cultures and the importance of matrilineal culture in Guam.

The third piece features another queer, CHamoru activist and leader, Naek, who is amongst the best-known, contemporary decolonial activists on island. The title of the piece: “Fanhoge” is an exhortation which literally means “to stand” (as a group), in this case for the rights and Indigenous sovereignty of CHamorus. It’s also the name of the “Guam Hymn” played at official events, and more recently, the deeply affecting hip hop refrain and choreography found in the “Protector’s Anthem” video produced by Nihi Indigenous Media. A stalwart activist, Naek’s unapologetic activism for CHamoru rights ranges from teaching to organizing protests to fighting for or against legislation and policies that curb the rights of indigenous peoples in the Marianas and beyond.

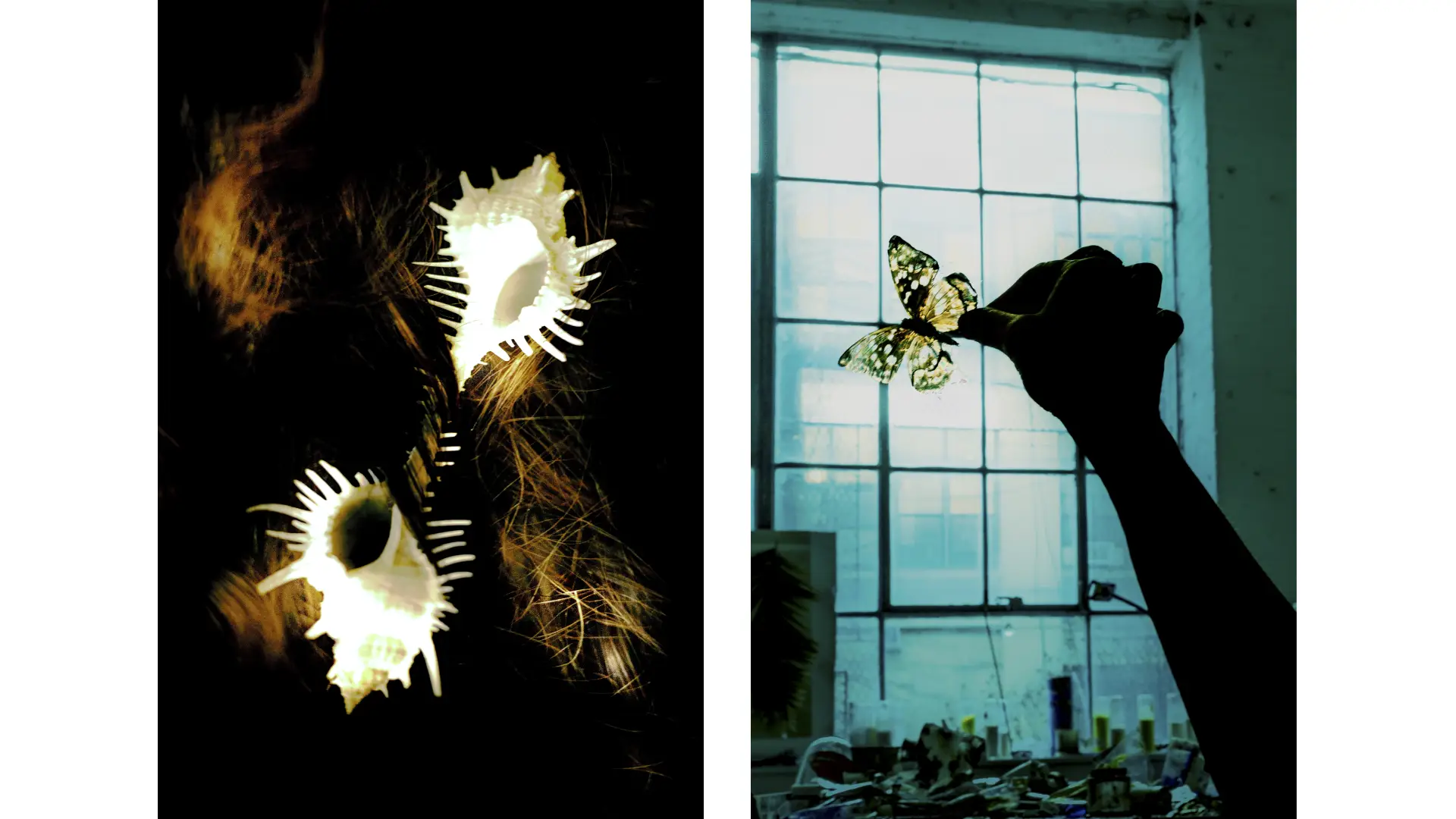

The sculptural piece you mentioned (Untitled) is made of resin and contains an audio file that plays excerpts from all of the CHamoru subject-collaborators featured in the original oil pieces with found objects. I cast and embedded multiple boar’s tusks, spondylus shells of varying sizes and a sinahi made by the Indigenous carver Hinennge, gifted from Vinessa (again, Mama Chai Apprentice). A CHamoru Intern/Studio Assistant and I painstakingly bubble-wrapped and duct-taped all of the pieces which I carried in a checked bag from Brooklyn to Honolulu. I then reassembled and basically (re)built the piece when I arrived in Hawai’i prior to the opening. The boar’s tusk was a gift from my Tåta (maternal grandfather) passed down to my mother who then gifted it to me. The spondylus shells came from Guam.

Your work also includes personal items of the subjects that I find so fascinating; some that include broken jewelry, even people’s teeth! Why is this important to you?

The way I interpret this aspect of my work is that I’m preserving objects associated with the lived experience of the subject-collaborator. Incorporating the pieces makes the final work feel more immediate because it includes something they’ve used or worn. The pieces also carry special meanings as they include pieces of jewelry and symbolize the transformation of pain into beauty.

I tend to emphasize subjects providing broken pieces or things no longer in use more as a tribute to and from the owner rather than being a treasured object that will be missed. Whether it’s a hoop (earring) that lost its pair or someone’s wisdom tooth, the object pays homage to someone who has lived, eaten wonderful meals, and added something to an outfit before leaving their home.

In effect, I ask people what they want to be remembered with, which is my subtle but arch retort to the historic practice of Westerners stealing Indigenous artifacts and/or elite institutions (from universities, museums, to monarchies!) refusing to rematriate them. These “consensual artifacts” also highlight the central role of gift-giving and reciprocity in CHamoru culture.

I do have to admit that I have a special place in my heart for donated teeth (which has been increasingly popular) because it riffs on ancient CHamoru artifacts which include human bone. Ancient CHamorros also used black and pigments to stain (often) incised teeth as an expression of status and beauty.

During your recent trip to Guam, you came back with soil, and dirt that you’d like to incorporate in your body of work. Why is this gesture important to you?

Like the use of medicinal plants in traditional healing, my decision to create pigments using soil or “dirt” from my Indigenous homeland underscores the sacred relationship CHamorus have to our land. By incorporating pigments from our island into portraits of those whose stories, objects and images I create, my goal is to ensure that the land stays with them and with it as a form of protection, as a talisman linking them to (our) home. I also can’t express how colorful our island is, or the way that the land produces indigenous flora which are incredibly fragrant. So my hope is to eventually capture not only the colors but also the scent of our land and landscape. Since our relationship to the land, sea and the sky is one that is ultimately familial in and with nature, and since our people are descendants of the first, long-distance ocean-going navigators, it felt somehow “right” to introduce what is for me, an exciting new step in my work. So for me, it’s also recognizing that there is both a “geology” and “genealogy” of pigments that I’m working with.

How does this sense of ownership and reclamation enhance the healing process for your subjects, and what does it mean to you as an artist to give them that control over their narrative?

In short, the ability to speak for themselves, to exert autonomy over their own bodies, images, and narratives is not only indispensable to healing, it is healing in its ultimate form.

I love how you describe it as 'booby trapping' visitors who engage with your work, with your paintings being motion-sensored so that when there's movement, the audio of your subject’s voice begins to play. What inspired you to incorporate sound into your pieces, and why do you feel it’s an essential element?

My training and my own experiences led me to reflect on how canonical and popular works of art of women and femmes never allowed or even asked us to think about their stories, who they were, or their relationship to the painter. There was so much erasure and silencing. When the beginnings of my practice emerged, I was also in a place where I wanted to be heard, myself. I simply couldn’t and wouldn’t accept or even conceive of exhibiting works without the inclusion of voice from that point forward. My goal, then and now, is to ensure that the portraits I make will never allow the women and femmes I paint to be separated from their own story, as they tell it.

I think your use of color is incredibly impactful, especially with the neon hues you mentioned being linked to the nuclear testing in the Pacific. The bright pinks, greens, and blues often appear throughout your work. Could you elaborate on how this color palette relates to that narrative?

In my earlier work, I intentionally used red, yellows, and pinks in under-paintings to allude to the (a) body. I always thought of the paintings as actual people rather than objects. I’ve since explored introducing colors associated with heat, incineration even, to pay homage to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (which marks 80 years this August 6th and 9th) and following decades of nuclear testing across the Pacific. Keep in mind that while my nearby Micronesian mañe’lu (siblings) in the Marshall Islands were the principal victims due to displacement, disease and death, CHamorus in Guam, like our relatives in Turtle Island on Indigenous lands, also died at much higher rates of cancer and other diseases due to being “Downwinders”.

It’s also crucial to remember that the U.S., Great Britain and France principally engaged in nuclear testing across Oceania between the 1940s to the late 1990s. For me, it’s a matter of honor to mark the grotesque and irresponsible travesties of war on Pasifika peoples in my work.

When you’re not painting, what are you doing?

Sleeping, traveling, researching, museum-hopping and hanging out with friends including a small group of incredible Brooklyn-based CHamoru women. I’ve also been spending a lot of time at the New York Public Library in the photo collection lately. Plus, hanging out with my two cats who hate that I do travel a lot.

Amongst the many items you have in your studio, what is the most near and dear to you?

My tea kettle! From making tea to miso soup it keeps me calm and nourished in the studio.

Is there an item you possess that you cannot live without or have in your studio as comfort or good luck charm?

I could go on for a long time, but briefly, shells from Guam and most recently, a boar skull from my Uncle Frank’s ranch, where the boar tusks I cast for my audio sculpture also came!

As you continue to evolve as an artist, what themes or projects do you feel compelled to explore next through jewelry?

For me, shells have always been a source of fascination. Not only do shells link me to my oceanic ancestry and especially the broad sense of “family” that exists in Pasifika cosmology but the aesthetics of shells and the striking array of colors, shapes, and designs move and inspire me. Even more than their beauty, I think it’s also important to remember that shells always reflect and draw upon the environment they find themselves in. So even as they are faced with existential threats from climate change toxic pollutants (along with our seashores, land and marine life) they quietly manage to create beauty while also serving the function of being someone’s home. The idea of designing jewelry pieces that speak to the beauty, tenacity, and protection that shells embody is definitely something that beckons me as an Indigenous CHamoru artist. In other words, it goes far beyond being pretty objects per se.

Is there a medium you're curious about trying out that you typically don't use/work with?

It’s been a minute, but I worked with bronze years ago but haven’t had access to a foundry for several years. I loved the process of starting with soft materials like clay and producing something hard as a final piece: in other words the duality and transformation that the medium allows.